Valid Reasons for the U.S. to Be, or Not to Be, Part of a Multi-National Conflict Management Force

The United States has been in an interesting position within the international community for the last two decades. With the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the US became the sole global superpower and ushered in a new, unipolar era. This unprecedented environment continues to present the US with an interesting problem; how does it deal with the notion of multilateralism, especially when dealing with conflict management?

Leading the Way?

An interesting dilemma within the conundrum of multilateral participation on the part of the US is whether the US is behind or ahead of the curve with regards to multilateralism. Depending on perspective, an argument could potentially be made for each.

Take the case of Kosovo. The US predominantly made up the NATO force that conducted ten weeks and over 38,000 sorties [1] and provided 650 of the 927 NATO aircraft.[2] This operation did not have United Nation’s support, primarily due to the belief that Russia would veto any such action within the UN Security Council. Therefore, through NATO, the US pushed for the use of military strikes to coerce Bosnian actions with regards to the Albanian population in the Kosovo province. Following the controversial conflict, the UNSC passed resolution 1244, authorizing “relevant international organizations to establish the international security presence in Kosovo,”[3] thus providing a UN mandate for the NATO Kosovo Forces (KFOR).

70% of the air forces used to conduct Operation Allied Force were American, and while all NATO members participated in the operation to some degree, this was a US campaign attempting to manage the Kosovo conflict. One could easily argue that it was US action that fostered NATO and UN participation since these regional and international institutions followed the US’s lead in the conflict. However, the argument could also be made that the US did not fully engage the UN completely and used NATO as a cover of multilateralism while really acting independently. So was the Kosovo conflict a case of the US elevating itself to international interaction or degrading itself so as to conform to international pressure?

Who Says?

Consider further that this highlights another relevant question; how does international law fit into the equation? Russia and China both played prominent roles in preventing the Kosovo question from being fully addressed within the UN Security Council.[4] Because of the structure of the UNSC, this opposition effectively ceased further action on the issue on the part of the council. As a result, the US bypassed the Security Council and chose to form a coalition of its own making, in this case through the regional security organization NATO. But this is technically in violation to international law and is one of the predominant contentious issues that question’s the legitimacy of the operation.

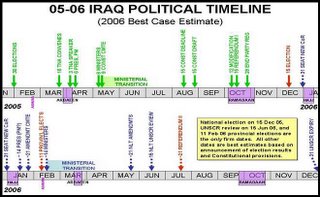

Fast forward to the development of the Iraq War in 2003 and it is a case of déjà vu. The US and the United Kingdom pursued within the UNSC a resolution geared towards forcing the Saddam Hussein regime to abandon its Weapons of Mass Destruction programs. Opposition to resolution enforcement was led by the French, and again due to the structure of the UNSC, the issue was at an impasse and the US therefore bypassed the Security Council and developed a coalition of its own making.

The structure of the UN and the composition of the UNSC have coalesced into what could arguably be called a fatal flaw in the system. Because the UN is the only recognized comprehensive international security organization that is authorized to address any interstate crisis, it is in the unique and solitary position of managing conflicts. Yet because of the veto powers of the permanent members of the UNSC, geo-politics and state interests greatly impact the ability of the council to address global crisis.

In addition to the examples of Kosovo and Iraq, the UNSC was relatively ineffective during the Cold War as the US, UK and France stood on the opposite side of the Soviet Union and China. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, and with the rise of Chinese influence, coupled with the geo-political ambitions of France, the UNSC has become an extremely volatile and unpredictable environment. So as the US addresses conflict management and its decision to incorporate other international actors, it must understand the dynamics and politics of the UNSC.

All of this impacts US policy as the state contemplates unilateral or multilateral action. A current example of this is the situation in Darfur, Sudan. The US is calling for international action, going so far as to call the violence in Darfur genocide. However, the West has been tenuous at best as it examines the situation. Currently about 7,000 African Union troops are operating in Darfur under a very limited mandate,[5] with most observers calling this force woefully inadequate to deal with the crisis. Moves to incorporate UN troops have received intense pushback from the Sudanese government, which according to some is complicit with the violence. To further complicate the issue is the fact that Sudan is the largest foreign oil project for China, who also happens to be the largest weapons supplier to the Sudanese government.[6] So the dilemma for the US, as well as the rest of the international community, is how to address the issue through the UNSC and in the face of China’s veto. This dilemma is replicated with the Iranian nuclear crisis as Iran recently signed a $70 Billion dollar oil deal with China.[7] Because of China’s growing thirst for oil and its heavy investment in these troubled locations, China simply will not allow Sudan or Iran to be impacted by UN sanctions, which would effectively eliminate China’s investments and restrict its access to these energy sources. This presents the international community and the US in particular, with two more crises that may not be able to be addressed by the one institution that was designed to deal with them.

Hard or Soft?

The bottom line with regards to the UN is that it is plagued with conflicts of interest. These conflicts of interests extend to every nation within the organization, but are most apparent and felt in the permanent five members of the UNSC. Therefore the interaction of the UN and the UNSC specifically, will always be limited, as it will be forced to address conflicts that do not garner direct and opposing views on the part of the permanent five members of the UNSC.

So when the US examines policy options with regards to conflict management, how should it decide on who, if any, to incorporate into the process? This decision should be largely based and driven by effects. Once the effects desired have been established, the state can then decide on what conditions then lead to these effect-objectives. After recognizing the desired conditions necessary, the US must then decide on the actions needed to create those conditions. Those actions will either be based on America’s hard or soft power. It will be that determination that will largely dictate whether the US should pursue unilateral or multilateral avenues.

The US boasts the worlds most powerful military, advanced and capable beyond the dreams of most worlds leaders. It is also home to the most power economy in the world. This constitutes considerable hard power and provides the US with many options for achieving its policies. The US is also known as the leader of the free world and as an icon of liberties, freedoms and opportunity. It is these qualities that allows the US to convince or persuades a foreign state that our goals should be their goals. This is soft power and it is not dependent on the capabilities of the state but on the foreign perception of the state.[8]

It is this reality, perception versus capability, that drives the paradigm needed to develop effective policy towards a conflict. Hard power versus Soft power, which can be focused as unilateral versus multilateral. Hard power depends on military and economic capabilities and is intended to coerce another state towards a certain action through either force or treasure. Soft power on the other hand is dependent on the intangible of perception, particularly that of the people. So the US could use the military to coerce a state to hold elections or its own government could serve as an example to the people of that state who then force their own government to hold elections. Both achieve the desired action of elections, but it is soft power that properly addressed the required conditions needed for the elections to occur.

Conclusions…

Within the preamble of the 2006 National Security Strategy, President Bush states that US national security strategy is founded on two pillars. “The first pillar is promoting freedom, justice and human dignity,”[9] all primary elements of Soft power. The second pillar is, “confronting the challenges of our time by leading a growing community of democracies.”[10] This second pillar of confrontation revolves around tangibles or elements of Hard power. The significance of Soft power as the first pillar shows a conscious effort by the US administration to at least theoretically constrain its enormous economic and military advantages while soliciting global buy-in towards the US position with regards to a conflict.

So when does multilateral conflict management work for the US? For one, when the conflict is controversial. If the legitimacy of the US position is in question, then US Soft power is under threat. Therefore an effort needs to be made to manage the conflict with as much of a concerted effort and with as many allies as possible so as to reinforce legitimacy. This was seen with regards to the Kosovo conflict and the incorporation of NATO. Secondly, conflicts that are dependent on reconstruction and reconciliation typically require multilateralism. This has been a shortfall for the US with regards to the current Iraq conflict. While the US was more than capable of dealing with the invasion, and it did so quite effectively, it has not been as successful with the reconstruction portion of the mission. This lack of success is due partially to the lack of legitimacy the US has in Iraq as well as the nature of the reconstruction mission itself. Finally, the US should search for a multilateral approach when the nature of the mission is specialized to a point that the US is not fully up to the task itself. While the US is improving, an example of this is peacekeeping operations; an operation the US has been slow in accepting and performing. All of this is of course under the umbrella of international legality, which if is lacking will inherently complicate the ability to garner multilateral support anyway.

As the second pillar of the 2006 NSS states, the US will continue to lead the way in addressing global conflicts but it highlights that, “history has shown that only when we do our part will others do theirs.”[11] The obvious implication in this is that unilateral US action is not a snub towards multilateralism but rather a drive to force multilateral participation. Kosovo again serves as a good example of this.

Of course many tangible reasons exist to incorporate multilateral action, to include the conflict cost-sharing factor and increased troop deployment numbers; and they can be serious contributions to a conflict. For instance in the 1991 Gulf War, the US had committed over 500,000 troops along with about 160,000 coalition allies who made up around 24% of the UN force. But the conflict only cost the US about $7 Billion rather than the roughly $62 Billions dollar cost of the conflict.[12] So the contributions of states in treasure to a conflict can be very important.

The US, as the most powerful state in the world is in the unique position of having its foreign policy, especially its management of conflicts, examined and criticized by the global community. Under this scrutiny, the US must ensure that its Hard power is used precisely and rarely while strengthening and projecting its Soft power as broadly and often as possible. By using this approach to conflict management, the US maximizes its ability to leverage force or goodwill as appropriate. There are many valid reasons for the U.S. to be, or not to be, a part of a multilateral conflict management force, but the determining factor for that participation must be determined by what the US hopes to effect and how they intend to do it.

[1] Kosovo War. The NATO Bombing Campaign. Wikipedia Online Encyclopedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kosovo_War#Criticism_of_the_Case_for_War.

[2] Operation Allied Force. http://www.defenselink.mil/specials/kosovo/.

[3] United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244. Article 7. 10Jun1999. 4May2006. http://www.un.int/usa/sres1244.htm.

[4] Nye, Joseph S., Jr., “Unilateralism vs. Multilateralism: America Can’t Go It Alone”. International Herald Tribune. 13Jun2002. 2May2006. http://www.globalpolicy.org/security/peacekpg/us/2002/0613uni.htm.

[5] Q&A: Sudan's Darfur Conflict. BBC News. 5May2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/3496731.stm.

[6] Goodman, Peter S. “China Invests Heavily In Sudan's Oil Industry: Beijing Supplies Arms Used on Villagers”. The Washington Post. 23Dec2004. 5May2006. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A21143-2004Dec22.html.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Nye, Joseph S. Jr., “Propaganda Isn’t the Way: Soft Power”. International Herald Tribune. 10Jan2003. 4May2006. http://www.ksg.harvard.edu/news/opeds/2003/nye_soft_power_iht_011003.htm.

[9] Bush, George W., Preamble. The National Security Strategy of the United States. Mar2006. 5May2006. http://www.whitehouse.gov/nsc/nss/2006/nss2006.pdf.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Horan, Fred. “How much did the Gulf War cost the US”. Information taken from Conduct of the Persian Gulf War, The Final Report to the US Congress by the US Department of Defense; April 1992; Appendix P. Cornell University. 20May1997. 6May2006. http://people.psych.cornell.edu/~fhoran/gulf/GW_cost/GW_payments.html.